This is a modified version of a report submitted on Rwanda’s recent election.

Abstract:

This report reviews Rwanda’s 2024 Presidential and Parliamentary Election by Dr Jonathan R Beloff. The paper examines and analyses how Rwanda carried out its election. It provides insights about the final day of the campaign trail, the casting of ballots and vote counting. The research relies on data collected during a fieldwork period from 12 to 16 July. Research methods during fieldwork include interviews and conversations with Rwandans and ethnographic observations. This report provides observations, analysis and suggestions for future elections. Overall, it concludes that Rwanda conducted a relatively smooth election with no issues of voter fraud, intimidation or ballot stuffing.

Introduction:

From the 14 to 16 July, Rwandans went to the polls to cast their ballots for the President and Parliamentarians in the Chamber of Deputies. An estimated 8.9 million out of 9 million eligible Rwandans voted in the elections in Rwanda and internationally. As of 17 July, President Paul Kagame from the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) won the Presidential election with over 99% or 8.8 million votes. Opposition candidates Dr Frank Habineza from the Green Party and Independent candidate Philippe Mpayimana won 44,479 and 28,466 votes, respectively. At the writing of this report, the RPF won over 68.8 per cent of Parliamentary votes or 37 seats in the Chamber of Deputies, with other minority parties reaching between 5 and 11 per cent. The final vote counts were announced on the 22 July.

This report concludes that no violence, election fraud, or other problems occurred at visited polling locations.

Despite the relatively smooth operations of this election, it will receive international criticism as unfair and unfree. The election process has and will continue to receive international criticism as many accuse the Rwandan government of promoting a one-party dictatorship under the control of the RPF and President Paul Kagame. The accusations made against Rwanda’s elections broadly compose excluding potential oppositional candidates, voter suppression and intimidation, as well as fraudulent vote count. Despite many international news media, organisations on democracy, human rights organisations and individuals accusing the election as fraudulent, they did not take the opportunity given by the National Electoral Commission (NEC) to observe. While it is not proper to speculate their reasons not to do so, it likely stems from how witnessing Rwanda’s election will not benefit their existing narratives and conclusions about Rwanda’s political system.

After receiving permission from the NEC, I (Dr Beloff) travelled to Rwanda to witness the election process. Since December 2022, I have asked several Rwandans, mainly in Kigali and Musanze, their opinions of Rwanda’s political system and democracy. During recent fieldwork periods of December 2022 to March 2023; August to September 2023; March to April 2024; and June 2024, I interviewed or held conversations with Rwandans of different ages about their perceptions of Rwanda’s political system. These interviews were intended to establish a preset understanding of their beliefs, perceptions, and problems with the current political structures. Additionally, I observed how Rwandans engage on social media within the context of the political system, both in terms of structures (how the government operates) and politics (political party campaigns). Returning to Rwanda on 12 July and staying during the election permitted me to engage with Rwandans while they voted and witnessed the political process in person. This methodology was important as it prevented preconceived notions or conclusions from the Global North when studying Rwanda’s political election.

Overall, I conclude that no significant problems existed in Rwanda’s 2024 election that would signal fraud. I witnessed no voter intimidation, pressure or ill practices while the votes were cast and counted. As an observer, the entire process was transparent, with Rwandans willing to discuss why they were voting rather than who they were voting for. Nevertheless, there are ways for the election to be improved, which are suggested later in this review.

Methods:

This report relies on qualitative research methodology. The primary researcher, Dr Jonathan Beloff, is a Postdoctoral Research Associate at King’s College London focusing on the African Great Lakes region. While his research typically focuses on Rwandan foreign relations and the Campaign against Genocide War, his research capabilities allow for a wide range of topics. His first visit to Rwanda was in 2008; he began researching Rwanda in 2012. His research methodology uses qualitative research methods such as semi-structured interviews, conversations, archival material and ethnography. Dr Beloff approached Bonheur Bobo d’Amour Pacifique, a Rwandan, to assist in the research for this report. The two have known each other since 2012, when Mr Pacifique worked at the Kigali Genocide Memorial (KGM). Mr Pacifique provided translation support and helped Rwandans to identify their perceptions, beliefs, and opinions at the various polling stations.

Dr Beloff travelled to eleven polling stations in Kigali, Bugesera, Ntarama, Masaka and Kabuga on 15 July. As the elections were from 7:00 am to 3:00 pm, there was a logistical limit to the number of sites the two could visit. Appendix A has a list of the polling stations that were visited. Observations of vote counting were in Kabuga. Dr Beloff and Mr Pacifique presented themselves to the site manager at each site. After introductions, they requested to visit different voting rooms with an average of three per site. The two observers inspected the rooms to see if outside actors such as police, military or other security officials were in the voting rooms.

Additionally, Dr Beloff inspected voting booths to see whether outside influence could impact a voter’s selection. They would then talk to one to three staff workers and observe people, often two to five at a time, voting in each room within the polling station. Afterwards, they would talk to Rwandans, an average of two to ten, who were waiting in line or had just voted. A rough estimate of fifty Rwandans were interviewed on their opinions of the election. No Rwandan was asked who they voted for or for their identification. They used every measure to protect all individual rights, and no names were recorded in order to promote privacy. The research included ethical considerations prior to conducting any interviews or conversations. Dr Beloff did visit an additional polling site on 16 July in Gisozi, Kigali.

Dr Beloff analysed the collected data through a triangulation process and discourse analysis. Triangulation utilises different sources of data to find underlying correlations and themes. Discourse analysis focuses on the use of language and terms to uncover understanding. These methodologies for processing the data are still in the early phases. Beyond this report, Dr Beloff will be submitting at least one academic journal article on the election and a blog post for his website for non-academic readers. Triangulation and discourse analysis will be utilised in the writing of these articles.

It is important to state how no polling site prohibited Dr Beloff or Mr Pacifique from observing the election, whether in terms of voting or counting ballots. There were no obstructions in asking questions, and many election workers provided full access and responses. Neither observer provided prior notification to visited polling sites.

Background:

Rwanda’s pre-colonial political system relied on the jurisdiction of the Mwami, translated as ‘King’. The political system relied on the Mwami, with their chiefs running much of the kingdom at the local level. Most hills, villages, or locations had three chiefs who would implement political rulings and govern, all subject to the Mwami. With the arrival of European colonisation, first by the Germans in 1884 and later by Belgium in 1917, the powers of the Mwami were privately minimised while publicly still being seen very much as the law of the land. However, actual political power rested with colonial officials. The Mwami often became either a puppet or a scapegoat for European powers to avoid local anger and responsibility for their frequently brutal policies. Rwanda’s 1961 referendum on the monarchy signalled the end of its rule while the nation turned into a republic. The following election that year for Parliament saw the Parti du Mouvement de l’Emancipation Hutu (Parmehutu) gain a majority of seats in the newly established Parliament. Its leader, Grégoire Kayibanda, became Rwanda’s first President after independence in 1962. His First Republic (1962-1973) witnessed greater authoritarian control and the dismissal of oppositional political parties following subsequent elections. In July 1973, Minister of Defence Juvénal Habyarimana instituted a coup d’état, removing President Kayibanda from power. He quickly established his political party, the Mouvement Révolutionnaire National pour le Développement (MRND), and banned other political parties such as the previous Parmehutu. President Habyarimana and the akazu, loosely translated as ‘little house’, dominated Rwanda’s political landscape until 1990.

During the early 1990s, Rwanda’s political space opened, with many parties establishing themselves. For instance, were the established parties of: Mouvement Démocratique Républicain (MDR), Parti Social Démocrate (PSD), Parti Libéral (PL), and the notorious Coalition pour la Défense de la République (CDR). Additionally, the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) established itself in 1987 after its Kampala Congress when it adopted its central political, economic and social plan of the Eight Point Programme. As described by Guichaoua[1], the early 1990s was a very turbulent political period. The Liberation War (1990-1993) and French pressure on Rwanda’s political space, sometimes referred to as Paristroika[2], led to significant instability within the existing political dynamics. The opening of political space allowed for extremist parties, such as the CDR, along with extremist elements in the non-Habyarimana (MRND) parties. Political assassinations, intimidations and cancelled elections were common during this period. Despite the initial hopes for stability and peace after the August 1993 signing of the Arusha Accords, Rwanda collapsed into genocide. The 1994 Genocide against the Tutsi began on the night of 6 April and continued until the Rwandan Patriotic Army (RPA), the military wing of the RPF, ended the genocidal massacres in the Campaign against Genocide War. However, up to one million Tutsis and non-extremist Hutus died. After the Genocide, a new government was formed on 19 July with a modified version of the past Arusha Accords. The changes mainly consisted of removing Hutu extremist parties such as the MRND and CDR. By 2000, Vice President and Minister of Defence Paul Kagame became President with a new constitution by 2003.

Rwanda’s 2003 Constitution shifted the nation’s political institutions. The President would have up to two terms consisting of seven years each. This changed in 2015, with the President only having five-year terms. The new Parliament contained two chambers. The lower, the Chamber of Deputies, consisted of 80 seats, with only 53 for elected officials. The remaining 27 seats are designated for women, disabled and youth officials. Elections are held every five years, except for the 2024 election, six years after the previous election. Unlike the lower chamber, the upper chamber, the Senate, consists of 26 members. They provide reviews of laws passed by the Chamber of Deputies. The NEC announced the 2024 Rwandan Presidential and Parliamentary elections earlier that year. Article 100 of the Rwandan Constitution states that, “Elections for the President of the Republic are held at least thirty (30) days and not more than sixty (60) days before the end of the term of the incumbent President.” Three candidates stood for President (incumbent President Paul Kagame, Green Party Leader Dr Frank Habineza and Independent candidate Philippe Mpayimana) with a total of six political parties (RPF, Liberal Party [PL], Social Democratic Party [PSD], Ideal Democratic Party [PDI], Democratic Green Party and PS-Imberakuri) and one independent candidate (Janvier Nsengimana). The election took place between 14 to 16 July. Voters from the diaspora voted on 14 July, with Rwandans in the country voting on the following 15. The final day of voting, 16 July, consisted of the 27 special seats for the Chamber of Deputies.

Rwanda’s political environment is mired by international criticism alleging Rwanda is a one-party state controlled by the RPF, with President Kagame as an authoritarian dictator. Professor of Democracy at the University of Birmingham Nic Cheeseman and Human Rights Advocate Jeffrey Smith categorise Rwanda’s democratic elections as saturated in authoritarian practices in human rights abuse.[3] Professor Filip Reyntjens from the University of Antwerp consistently described Rwanda’s political system as a dictatorship with no political or electoral rights.[4] Human Rights Watch[5] and Amnesty International[6] also criticise Rwanda’s democratic practices. Their findings influence foreign governments’ engagements with the Rwandan government. For example, a 2017 Amnesty International report criticised Rwanda’s democracy as authoritarian and aimed in its report to influence US foreign policy towards Rwanda.[7] These critiques continued before, during and after the July 2024 election.

Election Campaign:

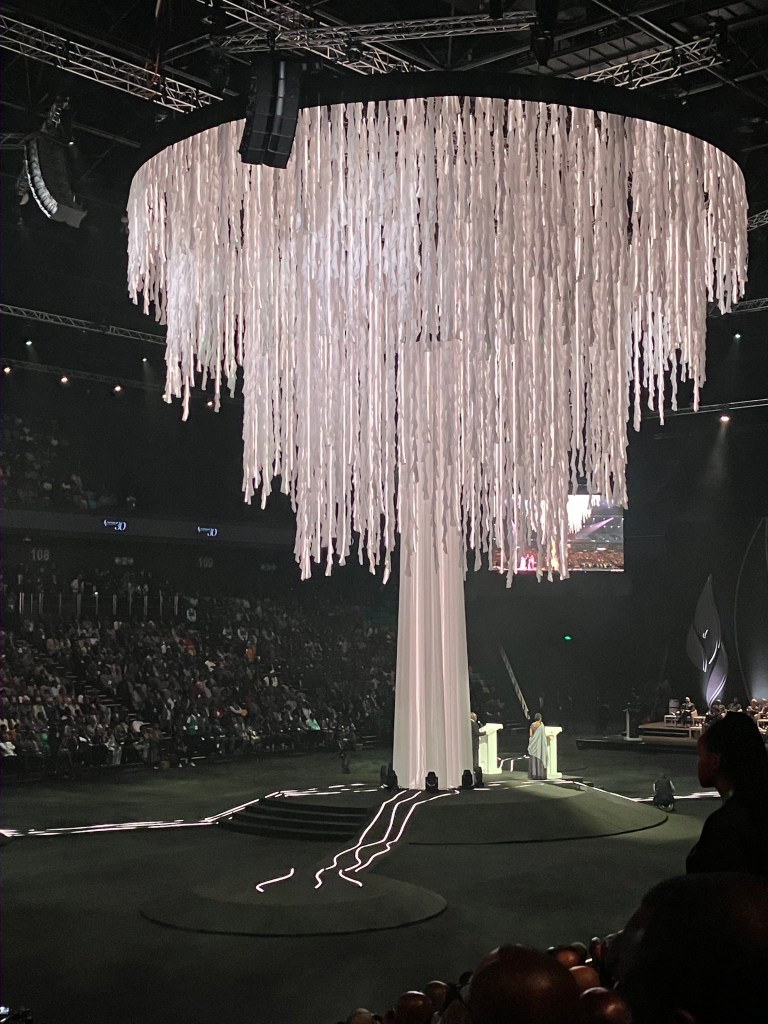

This section is rather limited as much of my exposure to the political campaigns came from social media and online articles. However, I arrived in Rwanda on 12 July, before the RPF’s final campaign rally at Gahanga. As I was unaware of the rally’s location, I went along with an official from the Rwanda Governance Board (RGB). Accompanying the RGB official was beneficial as he and others at RGB informed me of the procedures of Rwanda’s election and the institution’s role in ensuring a free and fair election. We arrived at the rally around 8:00 am with long traffic lines and tens of thousands of people already camped out at the venue. At the event, I spoke to roughly 20 Rwandans about why they were attending and their opinions of Rwanda’s democracy. Many commented on their desire to see President Kagame at the final campaign rally. For some, this was possibly their only time to see their President live rather than through the internet or television. Others commented that they wanted to ‘join the party’, a synonym for the rally. The rally’s environment was infectious as Rwandans danced and sang songs blasted on the speaker system.

The rally itself was a fascinating event in terms of messaging. The primary difference between the smaller parties and the other Presidential candidates compared with the RPF and President Kagame was rhetoric. The first group discussed public policy they would implement if elected. The RPF and President Kagame differed, focusing more on general slogans of ‘development’, ‘security’, ‘stability’ and so on. It was important to hear these keywords as voters would later use them as reasons for their decision to vote. However, little to no public policy recommendations were mentioned (based on the translation I received from a different RGB official). President Kagame’s campaign message was on how voters should continue to trust him and the RPF to continue Rwanda’s development since the Genocide against the Tutsi.

The rally illustrated the political realities of Rwanda. The RPF is the de facto political party for which Rwandans will vote. The other parties and Presidential candidates have to convince voters, through policy suggestions, why they should vote for them. The RPF does not need to campaign as the population is well aware of its track record regarding broad policies and decision-making. Many commented during the campaign rally and election that they trust the RPF to continue Rwanda’s stability, which is necessary for continued growth and development. There is a significant distrust in voting for political parties or actors unconnected with President Kagame. One older woman in her 70s commented on how the pluralistic political system of the early 1990s led to instability. It only ended after the RPF took power by ending the Genocide against the Tutsi. Thus, the claims that the RPF suppresses political parties and candidates are problematic as they do not reflect the reality of the difficulties faced by any different political party. Rwandans seemingly trust and will continue to rely on the RPF and President Kagame as they know their governance, policy, and security accomplishments.

Election Day – 15 July:

At roughly 6:50 am, we reached the Rukiri I APAPAC in Remera, Kigali. This was the first location of an intense day of visiting 11 polling stations. The polls officially opened at 7:00 am, but perhaps 50-75 people formed two organised queues. In front of the lines were election volunteers being sworn in. One volunteer later stated how important it was for the public to witness the swearing-in ceremony. It illustrated public transparency and openness to invite Rwandan voters and quell any hesitation about the election’s legitimacy. At exactly 6:59 am, the site manager finished the ceremony by lowering his elevated right hand. People began to swarm to the rooms designated for their particular villages. At first, It seemed confusing why these people queued just to race to their respective rooms later. Rather than forming a mob around the doors, they formed new lines again. All while the police were perhaps 20 meters away, the furthest they could physically be, from the voting rooms. At this location, only one police officer could be spotted, with another community security man keeping his distance.

After finding the site manager, as per procedure, he showed us one of the voting rooms and explained the voting process. Waiting voters lined up outside the room, with those in the front of the line having their identification cards temporarily taken. The elderly and sick did not have to wait in line as volunteers would bring them directly to the voting rooms. The election volunteer searched for their name in the register book. Once found, the first volunteer checked their names off the register, and they could come in. The voter would be allowed in and given back their identification card. Some polling stations would return the identification cards once the person had finished voting.

Nevertheless, at this and all the other locations, the voter would be given a white paper ballot containing the Presidential candidates. The ballots contained the candidates’ names, party affiliation symbols, party names and pictures, and an empty box. The voter would vote for their desired candidate in a private voting booth. A check mark or fingerprint in blue ink indicates the chosen candidate. Once the voter chose, they folded their ballot and placed it in a box containing a white lid and multiple zip tags. These tags prevented the boxes from being opened before the official counting of the votes.

After voting for President, the voter would be given a light brown ballot containing the different political parties and a single independent candidate campaigning for the Chamber of Deputies. The ballots were laid out similarly to the Presidential ones, with the only exception being that there were no pictures of any individuals. Voters collected their ballots and went behind a separate voting booth to cast their votes. Afterwards, they folded their ballot and placed it with a black lid in the box. Akin to the Presidential box, this box also contained zip tags to prevent tampering. Once they finished voting, the voter received a bit of purple ink on a finger or nail. The ink indicated that the person had voted. At some voting locations, the person’s identification cards would be returned to them. However, at most locations, they already had their identification cards. So, they departed the polling site, often first talking to people still waiting to vote.

Throughout the day, voters who had just voted or were waiting in line were asked questions about the election and international criticism of Rwanda’s political system. Only one woman in her early 20s refused to answer, but many others wanted to explain why they were voting. Many commented how they saw it as their civic duty to help promote Rwanda’s reconstruction since the 1994 Genocide against the Tutsi. Others remarked how they wished to be part of the political process. Interestingly, only 2 out of the at least 50 voters we spoke to explicitly stated which candidate they voted for, with others only stating why they wanted to vote. One expressed their duty to vote for President Kagame to illustrate support for his Presidency. History played a significant role in why some support Rwanda’s current political system. A middle-aged woman, perhaps in her 50s, commented how the instability of Rwanda’s political past in the early 1990s and up to the Genocide against the Tutsi influenced her voting patterns. Without stating explicitly who she voted for, she explained how the past instability led her to vote for the current establishment, which created and sustained stability and security. These two elements are necessary for any national development. The terms’ stability’, ‘security’, and ‘development’ were keywords used in the RPF’s campaigns. The frequency of their usage by voters who talked to us indicated who they were likely voting for without explicitly stating the political party or candidate. Perhaps the most interesting aspect of talking to voters was their desire to vote for rather than against a particular political party or candidate. Unlike in the Global North, where most voters often vote against a candidate rather than for one they truly support, Rwandan voters seemed to be voting for candidates and political parties they supported.

Many Rwandans shook their heads when asked about Global North’s criticism of Rwanda’s political system. A few voters became furious with even the question but calmed down once they realised the reason for it. The most common response was that international critics from human rights organisations, academics, news media sources, etc., needed to travel to Rwanda to witness the election. Many complimented me for my willingness to witness the elections and ask Rwandans questions. The engagement with Rwandan voters seemed to be non-existent with foreign-based observers. At one location, GS Gahanga I St Joseph A in Gahanga, a group of African foreign observers entered the polling site. The site manager later complained to us about how they did not follow protocol when reporting to him when they arrived. Additionally, they briefly went into a few voting rooms, made check marks on a paper and departed. One observer came to us for our opinions on the election and, more specifically, why we thought Rwandans were voting in the election. It seemed somewhat paradoxical that this foreign observer was more interested in our opinions than the Rwandan voters. When confronted about this issue, he quickly dismissed the need to ask Rwandans for their opinions.

Voters were also asked about the accusation made by those in the Global North of candidate suppression. Those interviewed dismissed the notion that any ‘serious’ candidate was denied the ability to campaign. Ndi Umunyarwanda influenced whether a candidate was considered as ‘serious’. Those who are seen as promoting ethnic divisions or genocide ideology were disregarded as not a ‘serious’ candidate. Their support for dismissing these candidates was seen as positive, as it illustrated how serious the Rwandan government was in promoting national security and stability. Critical political parties such as the FDU-Inkingi, Rassemblement Républicain pour la Démocratie au Rwanda (RDR), Mouvement Rwandais pour le Changement Démocratique (MRCD), Ishema Party and the Rwanda National Congress (RNC) along with their supporters based outside of Rwanda, are seen as ‘spoilers’ of Rwanda’s current political, social and economic development. In particular, the mention of Victoire Ingabire Umuhoza led those interviewed to roll their eyes, shake their heads or laugh at the name. Overall, no Rwandan commented on including these oppositional political actors in the election. Instead, they discussed their support for their exclusion as they are perceived as threats to Rwanda’s progress and a return to the failed political system of the early 1990s that led to the 1994 Genocide against the Tutsi.

Travelling to different polling locations allowed for a greater pool of responses from voters. All expressed how they did not feel forced or pressured in any way to vote. New and young voters between 18-30 years old expressed their excitement to vote. The RPF’s rhetoric on youth voting was in full force as this section of voters expressed their belief in the importance of voting with terminology similar to the Gahanga rally. However, there was no sense of blind support for the RPF. Rather, many commented on their support of Rwanda’s current development. One did mention how there were still serious problems in Rwanda, such as the rural-urban divide and unemployment, but felt the current government, i.e. the RPF and President Kagame, were best to solve these issues. As witnessed in every polling station, it was apparent that youth political outreach was effective.

The decision to visit multiple polling locations allowed us to determine whether there was consistency in the voting procedure. Consistency in the practices provides insights into whether election volunteers were properly trained. No polling stations were informed of our visit, with many site managers simply asking to see the observer identification badges. After briefly examining the badges, the entire polling station became open for inspection. We were allowed to ask questions to volunteers and voters alike. However, some other observers commented on how they faced inconsistency in access. While volunteers were friendly and completely transparent about the process, there was a greater sense of stress and exhaustion as the day continued. Many stations expected thousands of voters based on the registers, but by 10:00 am, hundreds to thousands of non-registered voters at the polling station arrived. This created more significant stress for volunteers who had to handle the influx of unexpected voters.

Throughout the day, polling stations blasted music with messages about the importance of voting, democracy, Ndi Umunyarwanda, etc. There were no songs from any political parties or campaigns. The speakers also made announcements for voters. These contained information about the location of certain voting rooms, for voters to see an election volunteer if they needed assistance or how there were so many hours before the polls closed. The music did provide what many called a ‘wedding’ atmosphere. While driving to search for certain polling stations, we often looked for banana stems and leaves set up near polling sites, a traditional way to indicate the location of a wedding within Rwandan society. Each voting room contained decorations. Some contained fairy lights, streamers, pieces of art, and fruit, and in one location, there were reeves on the floor. The decorations were organised by community leaders from the different villages. When asked why the rooms were decorated, one volunteer commented on how the voting booth should feel like a ‘home’. Others commented how these are items used at weddings. Interestingly, there seemed to be some notion of how the Rwandan population was in a ‘wedding’ with the political system, and thus it was a time for celebration. The notion of the ‘wedding’ could be seen in nearly every polling station. Like the RPF’s campaign rallies, the party atmosphere allowed community engagement. After voting, Rwandans could be seen meeting with fellow voters to discuss social gossip.

Throughout the voting process, we inspected voting booths to see whether there were any outside influences or applied pressures. None can be reported. Police presence was always minimal, with many seemingly focusing more on providing assistance in parking than anything else. All were kept a distance from the voting rooms and could only enter if requested by the site manager. However, no site manager stated the need for police assistance. Fundamentally, there was no police or security interference in the election, including any form of intimidation or threats. The only presence of RDF soldiers was at the Kigali Primary School in Kanombe, Kigali, but their presence stemmed from their need to cast their votes. After arriving at the polling station, they reached the front of the line but went through the same processes as any civilian. Once they cast their vote, they departed. One RDF officer commented on the importance of the military voting as they, too, need to perform their civil duty.

Overall, I can report no issues during the voting process. Once again, I did not see any form of voter intimidation. This includes any threats, pressures or influence by any political party or government official. All site managers provided transparency and were willing to answer any questions. It was noticeable that by 12:00 pm, site managers and volunteers grew increasingly agitated, but it was a result of the stress of the larger-than-expected number of voters. The site managers seemed somewhat unwelcoming at only two sites, but they quickly explained the stressful situation. As seen in the Criticism and Suggestions section below, more resources and increased capacity at polling stations are needed. Nevertheless, based on the polling stations we visited, we observed no issues with the voting.

At around 5:30 pm, we returned to the Rusororo Adventist Primary School in Kabuga (which had an estimated 7000 voters) to witness the counting of the votes. We originally had reached the polling station at 3:00 pm, but there were still hundreds, if not over a thousand, Rwandans waiting to vote. The site manager requested that we return within two hours after our inspection when, hopefully, the voting was finished. It would take until 4:55 pm for the final ballot to be cast. The staff were given 30 to 45 minutes of badly needed rest. Once the counting began, the observers and some locals entered different voting rooms. The site manager informed us that the NEC required that the preliminary election results be reported by 9:00 pm. Thus, there were only a few hours to count the votes. Each room contained multiple green posters with handwritten names of the presidential candidates. Another section of the board included the political parties for the Chamber of Deputies. Each vote would be announced with someone on the posters (taped to the classroom’s blackboard) checking off the number. One person would open the ballots (which were previously folded) and hand them (whether one at a time or a bunch) to someone who would read the name (first President and then Parliament). They would then hand the paper off to someone for them to confirm. This person then handed it to one last person who showed me each vote. There were between 3-6 people at the vote counting. After the counting was done, another volunteer displayed the empty box. The ballots would then be placed into them with new zip tags.

Once the count for the Presidential ballots ended, the volunteers turned to the Parliamentary ballots. They began to be read off and check-marked for each political party for which the ballot was for. The high number of RPF led to a minor mistake of the PL not being counted. I brought this to the attention of the counters, who fixed it. They then decided to pause after reading all non-RPF votes so they would properly be recorded. Once the votes were counted, the ballots and the green posters were locked in a room. NEC would pick them up after the special election on 16 July. When the counting was done, we went to each room to see the election results and whether there were any discrepancies from the results in the first room. At no point were we denied the ability to see the green posters. Some offered to allow us to look into the boxes that had yet to be zip-tagged. Overall, there were no severe problems in the counting of the votes or anything to suggest ballot stuffing.

Election Day – 16 July:

The final election day focused on the special seats for the Chamber of Deputies. This includes 24 seats for women, 2 for youth and 1 for people with disabilities. Unlike the previous day, this election is not open to the public. Rather, voters are community leaders in those special communities. I visited the APAPEC school in Gisozi, Kigali, to observe this unique vote. Only 67 registered voters could vote for a wide range of women candidates at this polling station. The voting process was akin to the previous day, except for only one voting booth, which the site manager explained resulted in fewer voters. The previous day’s ballots were locked away in a separate room at the polling station. It was clear through the window the zip tags on the ballot boxes to prevent tampering. Despite being perhaps 15 meters away, the sole police officer at the location had instructions not to let anyone enter the locked room. When questioned about the security of the ballots, the site manager dismissed the concern. He commented on how the likelihood of someone wanting to get to the ballots was minimal, the presence of the police officer, and how the vote counts had already been reported to the NEC the previous night (around 9:30 pm). The site manager then informed me how an NEC official would collect the ballots sometime in the afternoon. Akin to the previous day, I witnessed no vote tampering, intimidation, or ballot stuffing.

Criticism and Suggestions:

No severe comments or complaints exist as we witnessed how the elections were held freely and fairly. There are only a few critical comments on how the election occurred. These are presented with complete respect towards the Rwandan Government. Nevertheless, it is important still to note areas of concern and ways for improvement.

- Increased Polling Capacity:

- A serious problem observed during the 15 July election was the over-crowdedness of the polling stations and the volunteer’s exhaustion. Many site managers commented that while they prepared for a large number, the number of voters exceeded their capacity. Voting queues began at some voting stations, such as GS Gahanga I St Joseph A, at 4:00 am, three hours before voting began. Throughout the day, no voting station had less than 15 people waiting in line. However, the norm was for at least 25-75 people to wait. This led to voters waiting in lines from 30 minutes to nearly two hours. The wait resulted from the relatively slow process of collecting identification cards, checking registers, recording in overdraft lists and voting itself. At any given time, only two voters were in the voting room. The high temperatures, with some going beyond 30c, led to the dehydration of some waiting voters and volunteers. A few voters were seen suffering heat stroke and needing medical facilities. One site manager commented how they needed but could not open more rooms for voters to speed up the process.

The long delays for voters led to the election ending at Rusororo Adventist Primary School in Kabuga at 4:55 pm. This was nearly two hours after the official end of the election. While an announcement at 3:05 pm was made for voters to try other polling stations, Rwandans there refused. The site manager balanced the voting rights of those at the centre with the exhaustion of the election volunteers. Nevertheless, this led to delays and minor errors in counting votes.

Most polling sites should have used empty rooms for voting. Site managers commented on how they planned rooms to contain 400-750 voters each, but this number seems too large for the process. Thus, this report suggests that designated voting stations utilise all available space and increase the number of voting locations.

2.) Vote Counting:

- During the voting at Rusororo Adventist Primary School in Kabuga, there were minor problems with the vote count. The rooms contained poor lighting, forcing the volunteers to use their cell phones for additional light. Additionally, NEC needs to better train volunteers in vote counting, such as reading the names slower, to prevent mistakes. During the vote count for Parliament, I noticed how one vote was misread as RPF when it was for PL. I brought it to the attention of the volunteers, who corrected the error. From then on, votes for non-RPF candidates were read slower, with a pause before the next ballot. This comment does not suggest that there was voter fraud or purposely misreading of votes.

Conclusion:

Rwanda’s 2024 Presidential and Parliamentary elections witnessed over 7 million Rwandan voters casting their ballots for who they wish to see lead the nation over the next five years. This report relied on qualitative data collected at 12 polling stations in Kigali, Bugesera, Ntarama, Masaka, Gisozi and Kabuga, with a minimum of 50 Rwandans interviewed on their perceptions, beliefs and thoughts on the election and Rwanda’s political system. Additionally, the research relied on ethnographic methods to assess the election’s fairness. While international critics will make claims of the fraudulent nature of the election and the suppression of political candidates, this report concludes how I did not see any forms of voter intimidation, suppression or ballot stuffing to sway the election. This report does not deeply examine the allegations made by Global North critics of candidate suppression. Nevertheless, Rwandans were asked about this accusation, with all dismissing it. There were no police, military or any other form of security presence forcing Rwandans to vote for any particular candidate or political party. No RPF or political official forcibly influenced voters in casting their votes. The election should be considered as free and fair.

Appendix A: Visited Polling Stations

- Rukiri I Apapac Remera, Kigali

- Akabeza Remera, Kigali

- Busanza (Groupe Scolaire) Kanombe

- Kigali Primary School in Kanombe

- GS Gahanga I St Joseph A, Gahanga

- GS Gahanga I St Joseph B, Gahanga

- Ntarama GS, Ntarama

- Ntarama EP, Cyugaro

- Kanombe King David, Kanombe Kigali

- Wellspring Academy, Masaka

- Rusororo Adventist Primary School, Kabuga

- Gisozi APAPEC school, Kigali (site visit occurred on 16 July)

[1] Guichaoua, André, From War to Genocide: Criminal Politics in Rwanda, 1990-1994, (Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press, 2015).

[2] Beloff, Jonathan R. “French-Rwandan Foreign Relations: Depth and Rebirth of Diplomatic Relations.” The African Review 1, no. aop (2023): 1-26.

[3] Cheeseman, Nic, and Jeffrey Smith. “The Retreat of African Democracy.” Foreign Affairs (2019).

[4] Reyntjens, Filip. “Constructing the truth, dealing with dissent, domesticating the world: Governance in post-genocide Rwanda.” African Affairs 110, no. 438 (2011): 1-34; “Post-1994 Politics in Rwanda: problematising ‘liberation’ and ‘democratisation’.” Third World Quarterly 27, no. 6 (2006): 1103-1117; “Rwanda: Progress or powder keg?.” Journal of Democracy 26, no. 3 (2015): 19-33.

[5] Human Rights Watch, “World Report 2023: Rwanda,” 2024, retrieved from https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2023/country-chapters/rwanda

[6] Amnesty International, “Human rights in Rwanda,” 2024, retrieved from https://www.amnesty.org/en/location/africa/east-africa-the-horn-and-great-lakes/rwanda/report-rwanda/

[7] Amnesty International, “The State of Human Rights in Rwanda,” September 29, 2017; chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://www.congress.gov/115/meeting/house/106435/witnesses/HHRG-115-FA16-Wstate-AkweiA-20170927.pdf