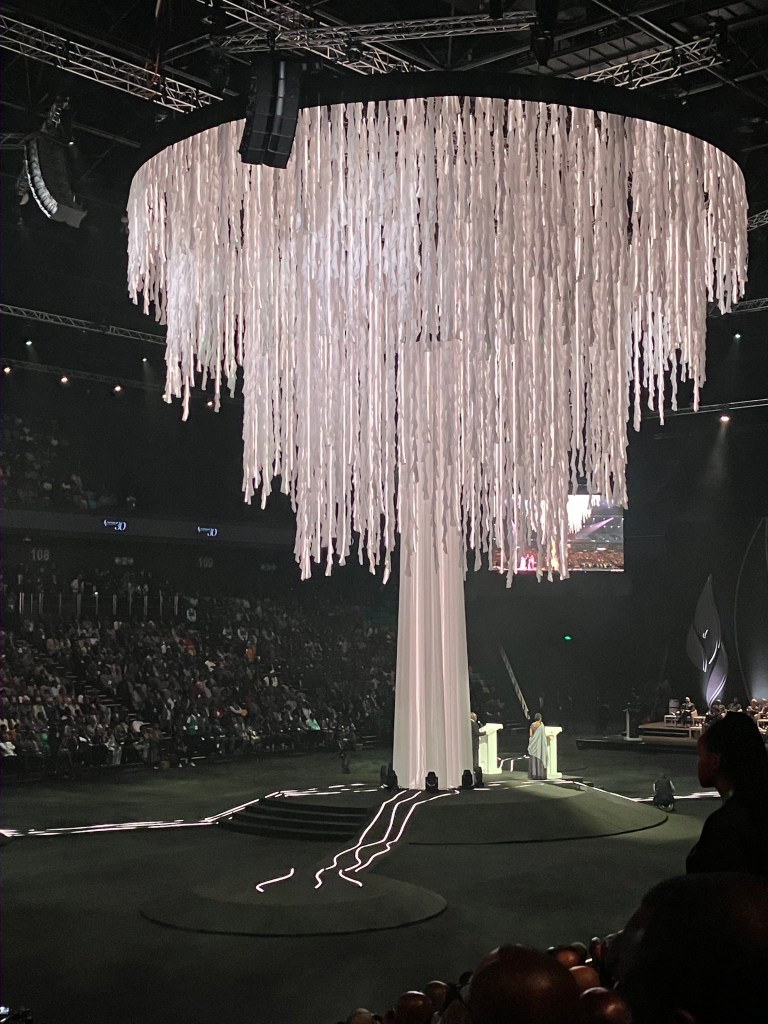

Kwibuka 30 Tree, which symbolises protection, aspirations, memory

It has been nearly a month since I attended Kwibuka in Kigali. The experience was truly unique as the main event, hosted at the BK Arena (as seen in the picture above), with speeches, dances and artwork that symbolised not only Rwanda’s horrific past but its desired future. While there are more experienced researchers focusing on commemorations (I highly suggest looking at the work done by Dr Samaantha Lakin), I decided to look back with my Political Science lenses. Baldwin, Longman, and others provide a more critical examination of Rwanda’s commemorations, so I decided to take a rather different approach to analysing this important event.

Rwandans are commemorating those who perished during the 1994 Genocide against the Tutsi. It has been thirty years since the Genocide ripped through Rwandan society, leaving up to a million Tutsi and non-extremist Hutus dead. This 100-day commemoration period, starting on April 7, the day which initiated the Genocide, witnesses Rwandan society remembering and reflecting on historical divisions between Tutsi, Hutu, and Twa. More importantly, it is a time for Rwandans to come together to promote unity and reconciliation under the banner of Ndi Umunyarwanda, loosely translated as ‘I am Rwandan’.

While it initially comes from Article 10 of the 2003 Constitution, its current policy iteration began in 2013 with the desire to foster national unity to prevent future divisionism and genocide.

The Rwandan government’s agency responsible for Kwibuka, the Ministry of National Unity and Civic Engagement (MINUBUMWE), will make this year’s commemoration a grand event as it is the thirtieth anniversary of the Genocide. Similarly to the twentieth commemoration, multiple international, national, and local events will be held with an eye on the neighbouring Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and the continuing social engineering of Ndi Umunyarwanda.

Tensions with DRC:

The recent wave of violence in eastern DRC has become ever so worrying for Rwandans. In an attempt to defeat one of the multiple Congolese rebel groups dotting the landscape, the DRC’s military, the Armed Forces for the Democratic Republic of Congo (FARDC), have increasingly been cooperating with Rwanda’s primary external security threat, the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (FDLR). This Congolese-based rebel group are the remains of the genocide perpetrators of Rwanda’s Genocide who wish to re-establish ethnic divisions, outlawed by the Ndi Umunyarwanda policies of ethnic unity, and return the country to that of the Genocide. The increased cooperation between the two actors has led to Rwandan concerns about increased military supplies and political legitimacy given to the FDLR.

The true threat posed by the FDLR is not its ability to try to defeat the Rwandan Defence Forces (RDF) and retake the country. The perhaps 2000-strong FDLR force has little strategic, operational or tactical capabilities to control Rwanda from President Paul Kagame’s government. However, their genuine threat stems from their ideology.

Former RDF Chief of Staff and recently appointed Rwandan High Commissioner to Tanzania Patrick Nyamvumba commented on the FDLR’s threat to Rwanda’s ontological security. As I argue in my book, the danger is akin to a mosquito that cannot do much harm to an adult human. Instead, it is the malaria they carry, i.e. genocide ideology, which poses the threat. Many within the Rwandan government are fearful that not enough time has passed to foster a resilient post-genocide unified identity that can fully expel the tempting ideology which composes the FDLR. Whether this is true or not can be argued, but the threat remains in the minds of Rwandan policymakers.

The second threat posed by eastern DRC is the increasingly genocidal language coming from the Congolese government. Congolese President Felix Tshisekedi has already called President Kagame ‘Hitler‘, but more troubling is his government’s language and actions against the Banyamulenge population. This group historically originated from Rwanda but has resided in Congo for generations despite facing past persecution. Over the past two years, violence against them, often from the FARDC and their FDLR allies, has seen the return of the Movement of March 23 (M23) rebel force from its near decade of inaction. However, the language coming from the Congolese government is worrying Rwandan policymakers.

Congolese Minister of Higher Education Muhindo Nzangi and government Spokesman Patrick Muyaya Katembwe have openly called for the persecution of the Banyamulenge. One Rwandan policymaker commented that the language coming from Congolese officials reminded him of language used by Rwanda’s perpetrators just before the Genocide. With this level of genocide ideology just to the nation’s west, the question is how serious the threat is to Rwanda’s post-genocide social reconstruction of Ndi Umunyarwanda.

Combatting Genocide Ideology:

Since the National Commission for Unity and Reconciliation (NURC), the predecessor of MINUBUMWE, the Ndi Umunyarwanda, the Rwandan government has continued implementing this policy to foster ethnic unity among Rwandans. This ideology follows the governing Rwanda Patriotic Front’s (RPF) interpretation of Rwandan history, which upholds Tutsi, Hutu and Twa as a form of socio-economic division rather than rooted in ethnic differences. However, Western scholars such as Reyntjens, Des Forges and Newbury dismiss this interpretation of history. Nevertheless, they miss an essential aspect of why Ndi Umunyarwanda exists. It exists as a mechanism for the country to move on from its past divisions to formulate ethnic unity that will prevent the environment of social divisions that can lead to a repetition of the Genocide.

Many within the Rwandan government, especially in the inner circles of power, are those who either fought to end the Genocide or were victims of it. The deep-rooted scars of their experience influence their desire for national social re-engineering. Many are still nervous that the past Hutu extremist ideology that promoted divisionism and hatred, which the FDLR still promotes, can override the progress made by Ndi Umunyarwanda and return. The comfort of scapegoating others for one’s problems is often tempting. The language coming from the DRC is worrisome for Rwandan policymakers, as it not only threatens the Banyamulenge but also follows patterns that once and possibly again inflict on Rwandan society. At least in the capital city of Kigali, the conditions for social divisions seem relatively minimal.

During my most recent fieldwork periods in Rwanda (December 2022-March 2023 and August to September 2023), I paid particular interest in whether Ndi Umunyarwanda had taken hold in the new generation of Kigali’s residents. During a 2016 PhD fieldwork, some government officials commented that it would take a generation or two for social unity to be achieved in the form of Rwandans being unconcern of one’s family, possibly Tutsi, Hutu or Twa identity.

While conducting fieldwork, I attended multiple social gatherings with Kigali’s growing middle class of Rwandans between the ages of 24 and 35. During conversations with fifty Millennials and Gen Z, it appeared that the government’s wish for the youth’s acceptance of Ndi Umunyarwanda had been effective. All attendees had little desire to bring up what they classified as their ‘parent’s divisions’ and instead saw each other as fellow Rwandans. These conversations illustrate the success of Ndi Umunyarwanda and, more broadly, the Rwandan government’s desire for post-genocide social reconstruction.

What will Rwandans Commemorate?

With the thirtieth commemoration, Rwandans will continue to examine their history of how the nation descended into Genocide through divisionism. Rwandan embassies and high commissions have and are still engaging with the Rwandan diaspora, while local villages continue to have relatively simple events to remember the past and help foster a united future. They need not look far to see the warning signs of how society can slip into scapegoating and securitising each other can lead to violence. The increased violence and ethnic-based language in eastern DRC are a steadfast reminder of the importance of Ndi Umunyarwanda. While the physical threats from across the border cannot be dismissed, internally, Rwanda is closer to Ndi Umunyarwanda unity rather than genocide divisions.