Kegel, John Burton. The Struggle for Liberation: A History of the Rwandan Civil War, 1990-1994, (Ohio University Press, 2025) ISBN: 978-0-8214-2627-2 (Link).

In 2019, I sat at Kigali Heights sipping a Mutzig (a local beer) with Lt General (Rtd) Caesar Kayizari. While we initially met when he was still Chief of the Army, within the Rwanda Defence Forces (RDF), it was during his retirement that he sparked an interesting question: how did Rwanda’s Genocide, known as the 1994 Genocide against the Tutsi, actually end? General Kayizari was one of the commanders of a combined mobile force (CMF), specifically Alpha CMF, which liberated large swaths of Kigali. Since his retirement, General Kayizari showed me different areas of Kigali and explained the military battles and rescue operations that took place there in 1994. By 2022, it sparked an idea that eventually led to my own research project on the subject. However, General Kayizari mentioned that someone else had already begun the research: John Burton Kegel.

Kegel’s relationship with General Kayizari served as a metaphorical ‘green flag’ for the authenticity of his research. Academia faces significant challenges, stemming from internal divisions, in understanding and critically engaging with Rwanda. As I wrote in a past article, the divide over whether to praise or condemn Rwanda, specifically its government under President Paul Kagame and the Rwanda Patriotic Front (RPF), is evident in nearly every piece of published material. In the past, some academics privately advised me that, to succeed in academia, one must find oneself on the ‘right’ side of this academic divide. This divide impacts researchers’ fieldwork, especially early-career researchers’, with many Rwandans commenting that they often feel Western researchers arrive in Rwanda with their conclusions already determined. However, Kegel does not fall into this trap as he seeks to understand and describe how the Rwandan Patriotic Army (RPA), the military wing of the RPF, won the Rwandan Civil War[1].

Kegel’s book, The Struggle for Liberation: A History of the Rwandan Civil War, 1990-1994, examines a relatively unexplored but vital period of Rwandan history. Akin to Gerard Prunier’s The Rwanda Crisis, Kegel’s book is a holistic examination of Rwanda and how conditions led to the formation of the RPF, which remains in power. However, Kegel presents an interesting historical parallel to Rwanda’s early post-colonial years with the 1990s Civil War. He argues that Rwanda experienced two significant periods of civil war. The second is the better-known Rwandan Civil War (1990-1994), but the first period is more interesting.

The original civil war began during the Social (Hutu) Revolution and lasted until the mid-1960s, ultimately leading to the defeat of the Union Nationale Rwandaise (UNAR) rebel forces from Burundi. Often, descriptions of the late colonial period focus on political divisions and the consolidation of Hutu ideology. Kegel’s description of the period is most convincing in sparking a new debate within Rwanda studies: should the period around Independence be considered part of a civil war, given that it encompassed many of the elements necessary to qualify as one? Within Rwanda, the Genocide against the Tutsi often receives its initial date during the Social (Hutu) Revolution rather than simply 1994. The reason stems from a modified understanding of Gregory H. Stanton’s description of a genocide’s lifeline.

An added note: there appears to be a rise in Rwandan historical books that attempt to rehabilitate the regimes of Gregoire Kayibanda (1962-1973) and Juvénal Habyarimana (1973-1994). Perhaps it is a tactic in a strategic campaign to try to discredit the RPF by disrupting their (and historical) narratives of the social and economic problems during those periods. However, it could be a genuine exploration of Rwandan history. Kegel never falls for this trap, as he provides a factually accurate account of Rwanda’s history prior to 1994.

Fundamentally, Kegel examines how history has shaped the RPF and Rwanda. However, we begin to encounter a blessing and a problem with the book’s research. The Struggle for Liberation utilises French, Dutch, British, American, and Belgian diplomatic records and cables, drawing on them in ways that go beyond any existing texts on Rwanda. The book describes and illustrates not only historical events but also how those serving at foreign embassies in Rwanda described the nation’s events. The only other person, I believe, who has done this type of research is Linda Melvern.

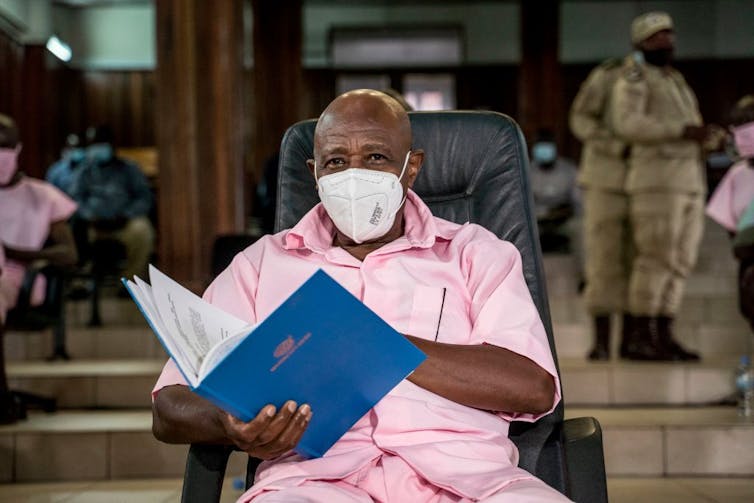

However, we encounter my first issue with the book: a lack of interview data. Kegel’s sources rely on diplomatic cables, existing information, and the interviews of a handful of people, all RPF. Those mentioned as the primary source of the interview data are Lt General (Rtd) Ceasar Kayizari, General James Kabarebe, Senator (Rtd) Tito Rutaremara and Christine Umutoni. While I hold the utmost respect (and friendship) with these people, there needed to be more voices, including those from the former Rwandan Armed Forces (FAR). When the existing interview data is properly utilised, it elevates the description and overall storytelling of Rwandan history. However, the book needed more of their voices.

This is where Kegel and my book differ. While he provides a more holistic examination of the RPF and Rwandan history, mine focuses more on the Campaign against Genocide War. It extensively utilises interview data from those who fought during the war, including RPA and ex-FAR members, to depict the various tactics, operations (humanitarian and military), and strategies of both sides. My book positions itself as a detailed exploration of Kegel’s Chapter 11, titled “The Campaign Against Genocide”. However, I do fully acknowledge the difficulties it would be for Kegel (or nearly any researcher) to gain the access I received while researching the topic. Nevertheless, I write this critique not to criticise the book, but rather to suggest how it could be elevated through greater use of interview data.

Another critique is what I previously hinted at, the Campaign against Genocide War chapter. This chapter describes the events starting with the assassination of Habyarimana until the RPF liberated Gisenyi, effectively ending the Genocide against the Tutsi. Unfortunately, the chapter reads as rushed compared to other chapters. Additionally, it lacks details of the RPA’s strategy compared to the ex-FAR, operational decision-making, humanitarian missions, the relationship between battles and tactics, and so on. All of these topics are mentioned and discussed, but only briefly. The reason I mention this issue is that many Rwandans are most interested in learning about this aspect of their history. Many want to understand not just the history of the RPF/RPA, but also how those forces liberated their home, village, town or city.

There are other minor critiques I have of the book, such as its portrayal of the ex-FAR. The limitations of the research methods are evident here as well. Kegel discusses some of the internal controversies among its officers, in part due to the diplomatic cables. However, it largely does not address the complex relationship within the FAR. For instance, the divide between Northern and Southern Hutus (something current Minister of Defence Juvenal Marizamunda experienced); perceptions of the Arusha Accords or even how to categorise the RPF (Commissioner General of Rwanda Correctional Service Brigadier General Evariste Murenzi, who fought for the FAR, remembers being told in October 1990 that he was not fighting ‘Tutsis’, Mwami supporters or foreign invaders. Rather, his commander said they were fighting fellow Rwandans who were refugees.) These divisions are important as they greatly influenced decision-making during the Genocide by those within the military, and why some refused to participate in the massacres.

Rather than condemning these missing elements, it may be worth suggesting that our two books be read together. Where Kegel shines is where my own research could be strengthened and vice versa. That realisation is what makes this book even more enjoyable. Its level of historical detail will hopefully lead to new debates and research on how the RPA ended the Genocide against the Tutsi. One of its greatest contributions is how it should lead to new critical questions about Rwanda for us to understand better not only its history but how it exists today as it continues to rebuild and recover from the great horror of the Genocide.

Despite my minor critiques, I believe this book will be one of the great texts on Rwanda in the years to come. Akin to the previously mentioned Prunier’s The Rwanda Crisis, Kegel’s book will serve as a textbook for understanding Rwandan history. I highly recommend it, and then suggest either visiting my site or reading my book on the Campaign against Genocide War.

[1] Civil War is a general term to describe the Liberation War (1990-1993) and the Campaign against Genocide War (1994).